AJ’s official heart diagnosis is Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) and Unbalanced AV Canal. We have spent four years learning about AJ’s heart, learning what all the fancy medical terms meant, and there are times when it still amazes and confuses me. I really wanted to find a way to make it easier to understand his diagnosis and what each of the surgery stages are, not only for our friends and family, but also for others who may be trying to understand their own child’s diagnosis.

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome is a congenital heart defect. It’s something you’re born with, and it’s not something that is caused by the actions of a parent. During development of the heart, the left side doesn’t grow as much as expected. Ultimately this means that the left side of AJ’s heart is smaller than it should be.

AJ also has Unbalanced AV canal. This diagnosis isn’t something we often talk about, but essentially it means that in the middle of his heart, the blood from his lungs and his body mixes together.

Biventricle Repair for HLHS

Before jumping into the typical single ventricle palliation, I want to call out that there is an option for what is called a “biventricular repair”.

In a bivent repair they are able to recruit the weak/smaller side of the heart to function, allowing the blood to continue to flow like a normal four chambered heart.

Most kids that are eligible for a bivent repair have a borderline small side or weakness, but it’s not always clear cut like that. There is a lot more science and detail behind it, and as someone who has not gone through it, I will leave that one up to the people at Boston Children’s to explain.

I want to be sure to call out the difference between Bivent REPAIR versus Single Ventricle PALLIATION. Since the bivent repair ultimately allows the body to circulate blood “normally”, it’s considered a repair. The single ventricle palliation addresses, but does not fix, the problem at hand, which is why it’s considered palliative.

If you are a parent new to the world of HLHS and trying to understand your options, I urge you to ask questions about the bivent repair. Also, I would suggest you seek the opinion of one of the larger pediatric heart hospitals. Although we are a UIHC and CHOP family ourselves, at the time of writing this post, Boston Childrens is currently the most well regarded location for bivent repair.

Because of the way AJs heart is unbalanced (his left side is significantly smaller) and where his valves are, he wasn’t considered eligible for a bivent repair.

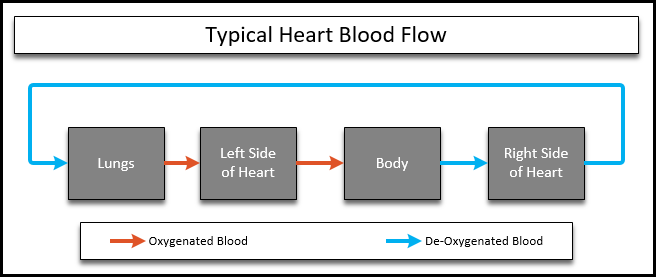

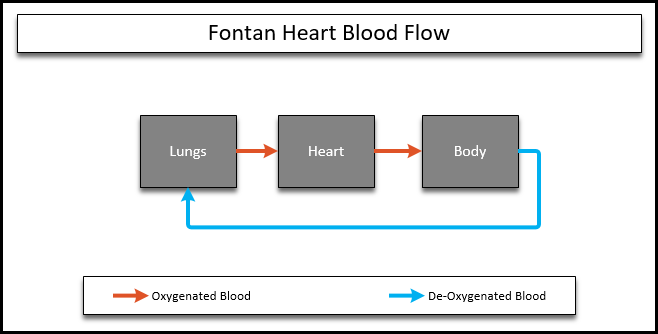

Typical Heart Flow

Before we move on, it’s important to understand how a typical heart circulates blood. Circulation routes blood to the lungs, left side of heart, body, right side of heart and repeats. There’s a separation between blood that has oxygen in it (oxygenated blood) and blood that doesn’t (de-oxygenated blood).

In a single ventricle palliation, the goal is to remove one of those stops to reduce the amount of work the heart has to do. The circulation then changes to skip the work of going back to the heart before going to the lungs.

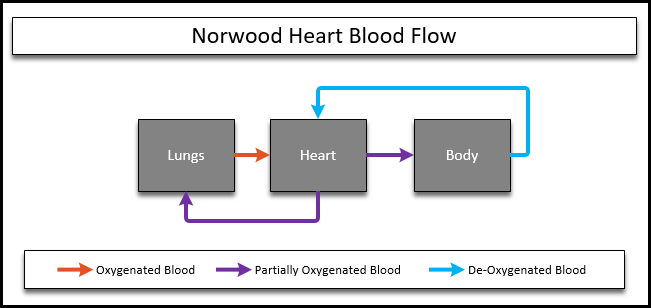

Norwood Heart Surgery – Stage One of HLHS Palliation

AJ had his Norwood when he was 15(?) days old, which is a little older than most children due to other complications and travel. The Norwood is the first stage of single ventricle repair. In this stage, the heart is re-plumbed so that one ventricle does all of the work of pushing the blood through the body. A “new” aorta is formed, a new path to the lungs is created by a shunt, and space is opened up between the two ventricles to allow them to work together.

Because of the opening of space, kids at this stage typically appear blue. During the Norwood stage, AJ’s oxygen saturations were 60-70% most of the time. That’s because the blood that flows out of a Norwood heart is a mixture of both oxygenated and de-oxygenated blood.

In AJ’s case, opening up space was less of a concern since he already had blood mixing in the center of his heart. That’s why from this point forward his unbalanced AV canal diagnosis is usually forgotten or at least not talked about often. It’s still “there”, but it doesn’t have the impact that it would if he had a more typical heart.

There are two different shunt types that may used – a BT shunt or a Sano Shunt. AJ has a BT shunt, which goes from the aorta to the pulmonary artery. Sometimes a Sano shunt is used and that goes from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery instead. It all depends on the setup of the heart and the pressures and other complex things that cardiologists and surgeons have to take into consideration, but the outcome is the same.

The Norwood sets the framework for the heart to work as a single stop circulatory pump in the future and allows time for the child to grow before future surgeries. The body eventually outgrows the shunt that was placed, and a new solution is needed. Typically the Glenn is next , but there are alternatives..

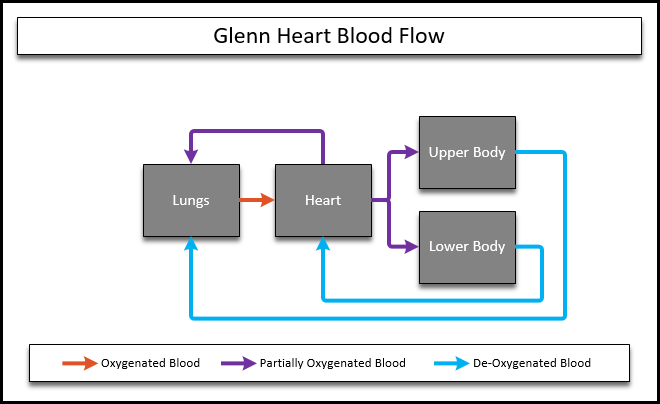

Glenn Heart Surgery / Hemi-Fontan Surgery – Stage Two of HLHS Palliation

In the Glenn stage, blood from the top half of the body is rerouted to skip the heart on the way back and will now go straight to the lungs instead. Blood from the lower half of the body still returns to the heart. Since there is still oxygenated and de-oxygenated blood mixing in the heart, kids at this stage will often still continue to appear blue, though typically less blue than the Norwood stage. Most Glenn children have oxygen saturations from 75-85%.

There are a couple variations of the Glenn / Hemi-Fontan that have evolved over time, most often the procedure is now technically called a “Bidirectional Glenn”, which simply means that the blood coming from the body is being sent to both the right and left lungs instead of only the right. Most parents and even medical professionals still tend to simply refer to it as the “Glenn”.

One of the common talked about nuances of the Glenn is that it often causes kids to have “Glenn Head”. Sometimes kids will have headaches or swelling due to the change in blood flow while their body adjusts.

In order for a Glenn procedure to be possible, the pressures in the heart and lungs have to be able to support it. If the lung pressure is too high, the blood won’t be able to flow and will cause a build up of pressure instead.

In AJs case, it was a struggle to get his pressures where they needed to be. The pressure in his lungs was high (pulmonary hypertension) which then caused his heart to have too much pressure in places to support the Glenn. At the time we started having these conversations, it looked really grim. We later learned that there are alternatives to the Glenn.

Glenn Alternatives

I can’t speak to all the alternatives at this (or any) stage of single ventricle repair, but there are options.

The larger shunt would have allowed AJ more time to grow and his pressures to improve before trying for a Glenn again later. Having a larger shunt placed still requires a lot more work out of his heart that the Glenn/Fontan circulation would. When we arrived at CHOP it was presented as an option if their tests continued to show that the pressure in his lungs may have been too high to support the Glenn.

Ultimately, AJ surprised us at the last second and his pre-surgery numbers indicated that he was ready for the Glenn.

Fontan Heart Surgery – Stage Three of HLHS Palliation

Typically the next surgery is the Fontan. Most single ventricle children have this procedure around three years of age, but it can happen when they’re older as well. The Fontan completes the single ventricle route, taking blood flow from the bottom of the body and returning it to the lungs, allowing it to skip the heart.

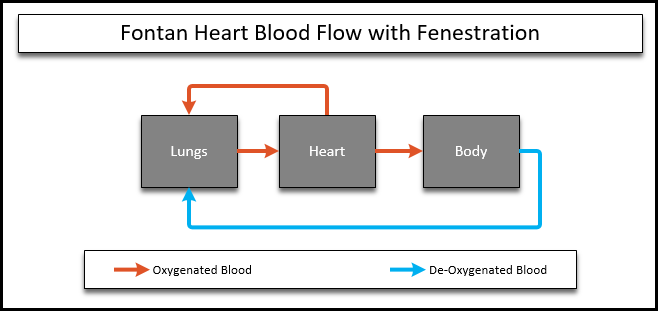

Sometimes if the pressures in the lungs or heart are still high, an opening (called a fenestration) may be left open that allows blood to flow from the heart to the lungs still.

After the Fontan, old and new blood are no longer both being sent to the heart, so the blood being returned out to the body is more oxygenated. Most kids end up having oxygen saturations that are in line with a typical heart, in the upper 90% ranges in most cases, with or without a fenestration.

Currently, AJ is not considered a candidate for the Fontan. His pressures put him at high risk, and it’s difficult to tell how much his medications might be masking a larger issue. For now, we continue to work on adjusting AJs medications and completing his airway reconstruction, while waiting to see what the future brings.

I know I mentioned it before, but it’s super important to note that completing the Fontan doesn’t mean the heart is “fixed”. Having a single ventricle heart increases risks in other areas. Liver and lung issues are relatively common because of how much pressure is built up in the circulatory system, and you can see how having a chest cold or pnemonia would be a much greater risk than it is with a typical heart. The heart itself is also having to work harder to push the blood through the circulatory system. It’s still better than the Glenn, but having a “fixed” heart is not something in the pipeline for AJ.

That said, there are a number of adults with HLHS and Fontan circulations, some of whom share their journey publicly. For more information about HLHS, we strongly encourage you to check out the following:

- Stephanie Romer runs CHD Legacy where she shares not only her story, but stories from others with various CHD’s as well. She is very active in the heart community, especially in advocating for ongoing care of adults with CHD’s.

- Meghan Roswick was previously a competitive gymnast and continues to be very active, both in terms of her sense of adventure and her desire to increase awareness and support through her Facebook page.

- There are also a number of active support communities on Facebook:

- HLHS Facebook Group

- HLHS/CHD family, question and answers

- HLHS/HRHS/CHD Support Group

- HLHS-Hope Facebook Page also has a Support Group as well, request to join.

I hate to say it – but just a reminder that we’re “only” parents here, and not medical professionals ourselves. We strongly encourage you to research any advice or information you receive online, from this site or others!